This post is the first in a three-part series discussing some allegorical images I created using an AI. For the background to these posts, please read Every Picture Tells A Story .

To start with, all we have are questions ... so many questions

The title of Allegory One seems off, somehow. Has there been a typo? Or is "afrAId" both a wink and a nod? A knowing wink to convey the idea that the painting has some enclosed double meaning; and a nod as to what this hidden meaning might relate to. But why shouldn't we be afraid, after all we have been told about the potentially existential risks posed by generative artificial intelligence (genAI),?

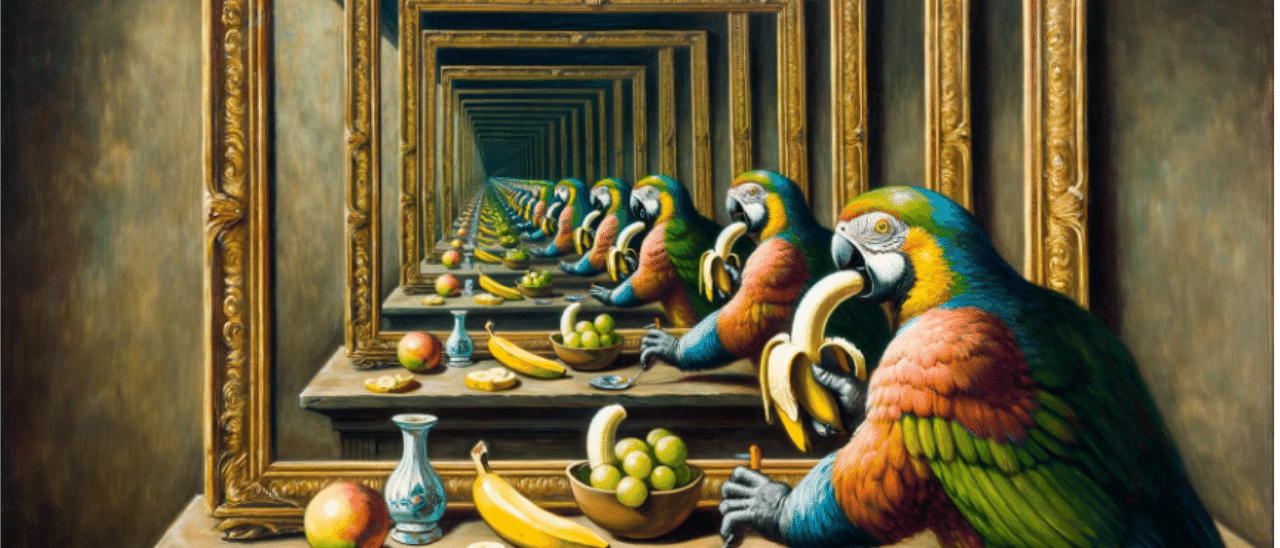

The picture's most obvious feature is the parrot, reflected over and over again in a “hall of mirrors” visual effect. Is the image receding away from us into the past, or coming towards us out of the future? Perhaps multiple attempts were required before the picture's creator got all the details right, finally resulting in the version of the parrot which appears to be closest to us, the viewer.

But why is it eating a banana?

Small things

Let's start with one of the smaller details: the weirdly curved and deformed silver spoon clutched in the parrot's rather manly left claw. I can't explain why the spoon is there. My instruction to ChatGPT was to create a classic still-life painting of a parrot reflected in a hall of mirrors while eating a banana. The software added the misshapen spoon all by itself.

This appears to be a small but telling example of an AI hallucination. I'm quite pleased to see it manifested here. It's illustrative of genAI's occasional habit of making things up.

From Steven Levy's newsletter for Wired:

Vectara’s CTO, Amin Ahmad, says an LLM creates a compressed representation of all the training data fed through its artificial neurons. “The nature of compression is that the fine details can get lost,” he says. A model ends up primed with the most likely answers to queries from users but doesn’t have the exact facts at its disposal. “When it gets to the details it starts making things up,” he says.

In this case, the AI is guilty of a two-fold error: the silver spoon shouldn't be there in the image (I didn't request it as part of the prompt for the picture), and the spoon itself is deformed and misshapen.

However, it may not be all bad: according to the Insight newsletter from Farrrer & Co., this accidental algorithmic creativity is becoming a fresh source of surrealistic inspiration for some:

As a newfound “material” for artistic creation, AI is frequently becoming the subject matter and focus of exhibitions at galleries and museums around the world.

Perhaps we might eventually see this trend grow into the 21st-century tech equivalent of Japanese traditional art, with its reverence for the principles of wabi-sabi, the art of the imperfect.

As it stands, the doubly imperfect nature of even this small detail seems to me to be precisely on point as part of the overall allegorical message; it's our first hint that, given this kind of flaw in the matrix, our current AI may not be such an existential threat after all.

Yes, we have some banana(s)

As already mentioned, the instruction to the AI was to draw “a parrot eating a banana”. ChatGPT4 (using DALL·E 3 as the drawing engine) created the image as requested, but spontaneously added extra bananas to the picture. I count three in total, plus some extra slices of banana strewn on the table.

Why are they there?

Their presence is an allegorical reference to another form of AI hallucination, a phenomenon known simply as "the Lone Banana Problem". The surprising fact is that (as at the time of writing), our current genAI tools cannot draw just one banana; ask ChatGPT4 or other tools such as the market-leading MidJourney to draw an image of a single banana, and it will (almost always) create a design featuring more than one.

The problem seems to be that our current AI tools lack an understanding of the physical world. According to David Hook, CEO of Digital Science, who first wrote about this problem:

The danger here is that due to the convincing nature of our interactions with AIs, we begin to believe that they understand the world in the way that we do. They don’t. AIs, at their current level of development, don’t perceive objects in the way that we do – they understand commonly occurring patterns. Their reality is fundamentally different to ours – it is not born in the physical world but in a logical world. Certainly, as successive generations of AI develop, it is easy for us to have interactions with them that suggest that they do understand. Some of the results of textual analysis that I’ve done with ChatGPT definitely give the impression of understanding. And yet, without a sense of the physical world, an AI has a problem with the concept of a single banana.

Perhaps this lack of understanding of the real world goes some way towards explaining genAI's problems with representing diversity. Hook characterises this category of error as a subtle form of software bias. His blog on the issue is worth reading in full:

For me, one of his standout points is on the implications of this bias in terms of risk management:

The use cases where we deploy AI have to be appropriate for the level at which we know the AI can perform and any functionality needs to come with a “health warning” so that people know what they need to look for – when they can trust an AI and when they shouldn’t.

I think this idea of a "health warning" chimes nicely with my suggestion for an approach to managing the risks associated with AI which adopts the principles of the Golden Thread.

And so to the parrot.

Stochastic what?

The Stochastic Parrot is the title of a paper notorious (in AI circles) for breaking the spell of general wonder and bewilderment at the seemingly impressive performance of genAI tools such as ChatGPT. At the time of publication, two of the paper's authors worked for Google; they were subsequently dismissed, for reasons which remain controversial.

As I understand it, "stochasticity" refers to a feature of statistics where the act of predicting the next result in a sequence of letters or numbers involves some inevitable degree of randomness and probability. Statistical errors or "noise" gets added to the predictions at every step, leading - on occasion - to poor guesses and false results.

This seems to be an inescapable characteristic of how genAI tools such as ChatGPT perform - repeating letters and words in pattern after pattern until finally coming up with something which seems statistically likely to be “the right answer”. This is a process which still requires a degree of human intervention.

According to further research based on the original paper, the metaphor of the stochastic parrot highlights some vital limitations of these tools:

The predictions made by a learning machine are essentially repeating back the contents of the data, with some added noise (or stochasticity) caused by the limitations of the model.

The machine learning algorithm does not understand the problem it has learnt. It can't know when it is repeating something incorrect, out of context, or socially inappropriate.

They go on to note that because of these limitations, a learning machine might produce results which are "dangerously wrong".[1]

As Santosh Vempala, a computer science professor at Georgia Tech, puts it:

“A language model is just a probabilistic model of the world ... not a truthful mirror of reality." - In defence of AI Hallucinations, Steven Levy, Wired.

I thought the image of the parrot endlessly repeated in the mirror was an interesting way to try and convey something about the principle of stochasticity as manifested in the Large Language Models (LLMs) that underpin our generative AI tools. The hall of mirrors effect represents all that our current AI can do: replicate but not originate until it produces a result deemed most likely to be correct (an outcome which still relies on human feedback).

Wait; there's more

The repeated reflections also make allegorical reference to another current hot topic in artificial intelligence: allegations that generative AI tools hold entire copies of images and texts in their vast databases, and are capable of reproducing them in their entirety, without due credit to the original creators. This seems to be the basis of the current New York Times copyright claim against OpenAI.

The case may turn out to be just a tactical twist, given that the Times was reportedly already in negotiation to license its content to OpenAI when it launched proceedings against the company. Any final outcome is likely to have implications and consequences that are many and varied.

What seems clear is that the nature of what we consider as "art" is changing, given the impact of new technologies. The advent of AI may mean that our current models of intellectual property and copyright are fundamentally broken. New models are already emerging.

Why I'm not afraid of AI right now

Chat GPT4 is impressive. I'm frequently astonished by its responses, which are often useful and sometimes almost transformative. But as our first allegory shows, it has inherent limitations, and it does make mistakes.

On this basis, Allegory One is a visual reminder that we should temper our expectations of the generative AI we have right now, much as we would manage our expectations of a particularly verbose and well-trained parrot. Given its habit of making things up; the problem of the Lone Banana; and the fundamental limitations of the stochastic technique, ChatGPT right now is probably about as threatening as a nonsense song:

We know that artificial intelligence is developing rapidly. For a forecast of some likely imminent developments, please take a look at Allegory Two: devices and desires.

Coda: It felt cruel, but I had to ask...

Me: Are you a stochastic parrot?

ChatGPT 4: "The term "stochastic parrot" is sometimes used to describe language models like me. It refers to the way these models generate text: by statistically predicting the next word in a sequence based on a vast amount of pre-existing text data. This process is inherently stochastic, meaning it involves some degree of randomness and probability.

While I am capable of generating coherent and contextually relevant responses, it's important to understand that my responses are based on patterns learned from the data I was trained on. I don't possess understanding, consciousness, or personal experiences. Instead, I analyze the text input I receive and generate responses based on statistical correlations.

So, in a metaphorical sense, you could say that I'm a "stochastic parrot," echoing back information and language patterns I've been trained on, albeit in a sophisticated and nuanced way that can mimic certain aspects of human conversation. However, unlike a parrot, I can process and generate language in a way that is responsive to a wide range of queries and can simulate certain types of reasoning and problem-solving."

Member discussion