I used to joke that it was the experience of seeing the film version of the musical Cabaret at an early age that "turned me gay."

In reality, of course it didn't. Baby, I was born this way. However, the movie did have an enduring impact. Its dark narrative, and the louche environment of 1930s Berlin in which it unfolded, was my introduction to a more adult realm of politics, performances, and possibilities of many kinds. Where what you see depends very much upon one's point of view. An idea which has stood me in good stead over the years.

One of the catchiest tunes from the musical is the KitKat club performance of "If you could just see her through my eyes", in which the composers Kander & Ebb satirise fascism with great wit and pointed charm. It's a political demolition job dressed up as a song and dance routine, an opportunity to poke fun at contemporary anti-semitism; mockery in a monkey suit.

I was reminded of the song by two stories in 2023.

One was the row about Bradley Cooper and his depiction of the composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein in the movie, Maestro.

The other was an uptick in public concern about the risks arising from the proliferation of "deepfakes" - phoney images and false videos on social media and elsewhere.

According to ChatGPT 4, "deepfake":

...refers to a technique for human image synthesis based on artificial intelligence technology. It's primarily used to superimpose existing images and videos onto source images or videos using a machine learning technique known as generative adversarial networks (GANs). The term "deepfake" is a portmanteau of "deep learning" and "fake."

Deepfakes are notable for their realism and have gained notoriety in various contexts, particularly in creating fake celebrity videos, revenge porn, fake news, hoaxes, and financial fraud. This technology raises significant ethical concerns regarding privacy, security, and the spreading of misinformation.

So, in the same news cycle, there were people concerned (outraged, even) that Cooper as an actor didn't look "Jewish enough" to play the formidable character of Leonard Bernstein; at the same time as other voices were expressing their fears regarding depictions of people as simulacrums that appear "too real"; impossible, perhaps to distinguish from the real thing.

Whereas no one else seems to have made a connection between the two different news stories, here at the Virtual Work blog we delight in comparing apples with stairs. It may even be my happy place.

The obvious concern about deepfakes is that they can - and are - being used to spread messages aren't true, to promote dangerous causes, and to incite actions or responses that the real person would not normally have publicly condoned, advised or encouraged.

Meanwhile, a number of people condemned Cooper as director for casting himself as the star of his film. Cooper simply didn't look "Jewish enough" to portray the great man. Sensibilities were particularly outraged by the news that Cooper was using prosthetics to give himself a nose which matched the stature of Bernstein's.

The argument - as I understand it - is that in order to portray a character such as Bernstein an actor would have to be Jewish themselves. And, ideally, Jewish with a big nose.

Which instantly made me think of the musician and actor, Sammy Davis Jr (who was Jewish, and had a big nose). What if it'd been possible to cast him to play the Jewish musician and conductor, Leonard Bernstein (who did indeed have a big nose, but wasn't black)?

Who might have been further outraged by that casting idea? If so, what do they make of colour-blind casting in general, as taken into mainstream theatre by the stage show Hamilton? A line of thought which brings us far too quickly into the whole area of acting and portrayal: Laurence Olivier blacking up to play Othello; Dick Van Dyke's English accents; Kevin Spacey playing a straight man ...

A digression

IMHO there were plenty of reasons why one might want to to walk out of Hamilton. I genuinely think it is a terrible musical, and Lin Manuel Miranda has been cloaked in the Emperor's New Clothes. The colour-blind casting for the London show I saw wasn't why I wanted to exit early; it was the work itself. I didn't actually walk out, although I would have been happy to leave at the interval if I'd been allowed.

Bernstein's own family were quick to respond, saying that they were happy for Cooper's work to speak for itself. But if casting one human to play another human can sometimes seem... problematic, perhaps we can now look to generative AI for an answer. Why not even do away with the human actor meat sack in TV and movies once and for all?

Obviously, the Hollywood actors with the collective power of their trade unions say No.

As soon as we start to think about machine-generated notions of portrayal we start to worry about bias and prejudice in the images depicted. Stereotyping of any form is always reductive, as well as potentially harmful. How loudly might the headlines have screamed if Cooper had used deepfake special effects to give himself the facial characteristics of Leonard Bernstein? An AI-generated "Jewface" (or any other kind of "-face") sounds completely horrific. But is our concern and outrage always focussed in the right place?

However.

Computer vision - how a machine is trained to recognise what it sees; and why it creates a particular image based on a specific request, seem to me to be quite closely related.

It's a subject I hope to look at more closely here on the blog. As I understand it for now, an AI tool doesn't "know" anything; it can only respond to an instruction by doing as it is told, based on what it has been told. Nowadays, tools such as ChatGPT 4 can create that response so quickly and comprehensively that it almost passes as "knowledge".

In my Film Studies course in the 1980s, we were taught that to the human eye, "reality is 24 frames per second". Perhaps in terms of AI, the equivalent is the size of the computer "word", the amount of encoded information that the software can ingest. As the technology continues to develop, the length of these "words" gets longer and longer. Bigger chunks of training data mean that there are more details for the technology to assimilate.

More detail = more reality. Or rather, a better understanding of reality. There is the potential there to deliver a more nuanced and seemingly more "intelligent" tool. Useful. But also the potential for more accurate and convincing deepfakes, and for more subtle and sophisticated forms of bias.

Once again, it all comes back to the information, the data on which the AI model is trained. It always pays to take a critical ethical look at the nature of that data, and the way in which it is managed. Looking for the possibility of negative consequences leading to potential harm for real people. We've talked before about the problems arising from algorithms based on data lacking in diversity and inclusion:

When it comes to images generated from data, the potential negative consequences - unintended or otherwise - are all too frequent and pernicious. They are also all too easy to overlook.

Take for example the robot imagery as featured on this blog. I ask the image generator for a picture of a robot doing a certain thing or in a certain situation; is it just me, or do the images of the robots themselves all come back as discernibly "male"?

If the answer = Yes, then query as to Why?

Information technology (in fact, any technology) in and of itself has no gender.

And yet.

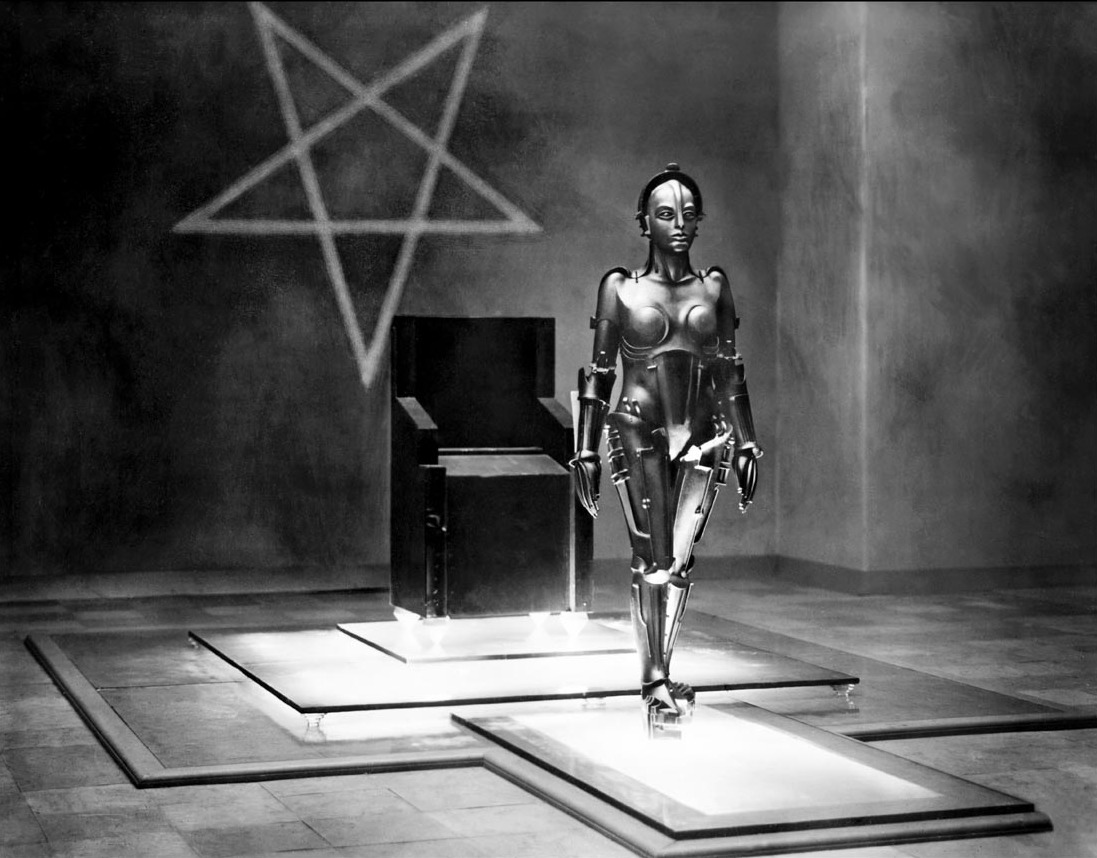

The reason "Why" in this case is probably not deliberate misogyny, encoded. It's more likely to be the unintended consequence of a training data set which perhaps did not include images of creations such as the Maschinenmensch, the ostensibly female robot played by an actress in Fritz Lang's Metropolis, and itself the idea of a German female novelist. Misogyny of a lazy, habitual and unthinking kind.

At present we seem to expect our AI to be better than we are ourselves. As a society we largely turn a blind eye to the number of deaths caused by human drivers on the roads; yet a single accident involving a machine-driven car causes widespread outrage and concern (in the incident in question, the pedestrian survived the encounter with an autonomous car; but the whole range of cars was still banned from operating).

Perhaps it is still just the shock of the new. But at some point, we need to stop ascribing god-like powers for deciding "right" from "wrong" to our AI tools. And as Gillian Tett in the Financial Times wrote: "Good robots must not be made to learn from bad human habits."

The machines may be faster and better than we are at spotting patterns, identifying trends and forecasting outcomes - but that is all. An AI must do as it's told, based on the information it's been given - by us. The machine can't resolve for human fallibility, credulity and illogicality. It won't fix ethical and moral issues for us; or rationalise our inherently relative and partial points of view. As the AI gets better and better at replicating reality, perhaps we will need to take a closer look at what we consider to be "real" ourselves.

After all, as Kander & Ebb conclude in their wicked little masterpiece:

If you could just see her through my eyes, she wouldn't look Jewish at all.

Member discussion