In July I took a tour of the Open Data Institute’s (ODI) latest Data as Culture exhibition, part of this year’s London Data Week. The ODI has a track record of supporting investigations by artists interested in the many and varied ways in which data shapes our lives and the world around us. The works on show took on various forms, expressing a vast range of ideas.

I missed out on seeing Ceiling Cat (an internet meme mashed up with ideas around mass public surveillance); and I was intrigued by Vending Machine, which, as per the programme notes,

" hints towards a time in the future when our access to food may literally be determined by data connected to wider political or environmental events."

I enjoyed the exhibition but came away still wondering: is this art as data, or data as art?

Cave art, decoded

The idea of connecting data about environmental events with regular access to food reminds me of a news story from January:

Amateur archaeologist helps crack Ice Age cave art code (from BBC News)

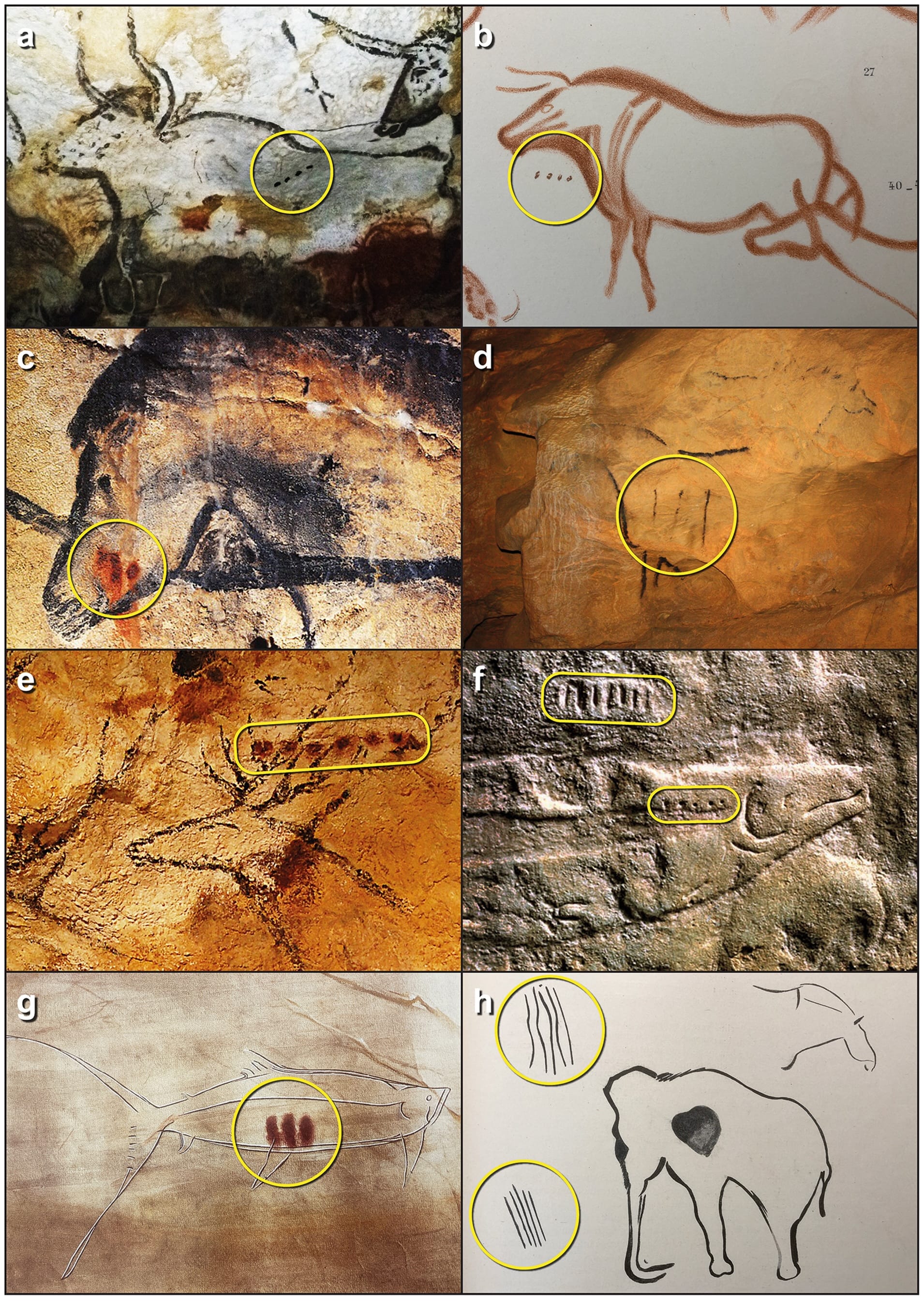

Ben Bacon, full-time furniture conservator and part-time researcher, has been studying images of cave art for years. He noticed that many of the symbols used in a variety of locations were similar. His discovery that the recurring marks can be mapped onto the lifecycles of the animals depicted caught the attention of several academic researchers; their findings have now been published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

Rather than the widespread and recurring use of the same set of symbols being nothing more than examples of Paleolithic clip art, Bacon et all suggest that the pictographs are predictive calendars, indicating when each type of animal is likely to be in season (and therefore when the best times are for hunting or fishing). In fact, they suggest that some of the cave paintings at Lascaux and elsewhere are early forms of information storage, sharing, presentation and analysis.

Mind. Blown.

Back in the day… a global phenomenon

Cave paintings, or “parietal art” are found all over the world. Europe, Africa, Asia, North and South America, Australia, and New Zealand. It's often extraordinarily beautiful. After touring some of the caves Pablo Picasso is supposed to have said:

"We have invented nothing."

My parents once had a paperweight which depicted wall paintings found in one of the great French cave complexes (probably...). Made of heavy, solid, crystal clear glass, with a translucent curved back and polished edges, when held against the light the ancient images of animals, plants and stick figures (which looked human, but might not have been) shone in remarkable clarity, even while their meaning and significance remained obscure. For a long time, I was confused: was this an actual chunk of the cave wall, encased in heavy, polished crystal? And what did the paintings and drawings mean - if anything?

Of course, eventually I came to understand that the object was (obviously) a replica - a well-crafted tourist souvenir. I still liked to stare into it, mystified by the imagery which at once seemed so remote but also somehow relatable. This was the era when Eric von Daniken's "Chariot of the Gods?" had us pondering about whether other ancient imagery - scratches in the high deserts of South America (only visible from altitude), and creative works from cultures long disappeared from view - were really the work of spacemen, aliens from another planet.

For a while, I fantasised that the cave paintings reproduced in my parents' paperweight were of similar origin.

Discovery: cave art = proto-writing

There are plenty of theories about the cave images; are they hunting manuals? Records or tallies of great events? Or the focus of worship? While attempting to interpret the images themselves, few researchers have paid attention to the series of dots, dashes and other recurring symbols which were added to many of the drawings and paintings of aurochs, mammoths, bison, deer and fish:

As Mr Bacon and his co-authors state, it has been accepted for some time that:

“… the use of sequences of dots, lines and other marks, often associated with animal images, reflected a widespread use of cardinal artificial/external memory systems in Upper Palaeolithic space and time…”

However:

“The actual subject of such systems—the information recorded in them—has been, so far, elusive."

After years of study, Bacon had the idea that the pictographs might function as a kind of calendar; one which predicts when specific animal species will come into breeding season and then subsequently give birth - important information for people who survive by hunting and gathering their food.

Bacon was studying cave art dating back to the European Upper Palaeolithic material culture spanning the period from 50,000 to ~12,000 years ago.

In other words: a hell of a long time before now.

What he and the research team discovered via his original insight and a lot of statistical image analysis is that the pictographs:

“ formed an efficient means of recording and communicating information that has at its heart the core intellectual achievement of abstraction.”

From this, they are able to assert that:

“The ability to assign abstract signs to phenomena in the world—animals, numbers, parturition, cyclical phases of the moon—and subsequently to use these signs as representations of external reality in a material form that could be used to record past events and predict future events was a profound intellectual achievement.”

As a result of this “profound” achievement, the researchers point to the way in which one particular symbol recurs in a way we now understand to be meaningful; as they put it, they may well have identified the first recorded use of a verb.

In other words: writing.

The research team go on to show that - based on Bacon’s original hypothesis - the pictographs can be understood as an early form of writing - an antecedent to the written forms of communication we take for granted today.

They conclude that this cave art may be a form of “proto-writing” which predates the previous earliest known writing system - the cuneiform of the Sumerians - by many, many thousands of years.

However as the researchers also point out, the cave art exists as a “visual system”; and for me, the images demonstrate the idea that it is the role of the artist to:

“point things out."

“It’s data, Jim”

As an OG Star Trek fan, I can never resist the urge to (mis-) quote a line or two. However, it’s this idea of data abstraction which interests me (and Mr Spock, probably) from a data science point of view.

The Cambridge University paper states that:

“ The pairing of animals/signs is evidence of the joining of multiple signs together in an ordered, rearrangeable, permanent and structured artificial/external information system, which used abstraction and symbols to convey complex information about the external world.”

So much of this language reminds me of the way in which we might describe modern data management – it's now commonplace for us to make use of “information systems” to collect and store “structured data”, which can then be ordered and re-ordered in ways which help us better understand the complexity of the world around us.

Much of which chimes with my personal working definition of “data” as:

Perhaps we can understand these images as the stored answers to some recurring queries that must have been important to human life at the time:

- When is this animal in season?

and - Which animals are in season, when?

Another use case for AI?

“Art as data” is certainly not a new theme. We may think of data visualisation, infographics and so on as modern inventions; even though contemporary practice can trace its origins back to campaigners such as Florence Nightingale (now somewhat notorious in data visualisation circles for the way in which she manipulated the presentation of statistical data on fatalities from war injuries to suit the purposes of her own campaign).

From the work of Bacon & co, we now understand that the use of art to convey important information about a complex world goes much further back than we previously believed.

Their statistical analysis of the cave art imagery goes well beyond the limits of my understanding; but one thing I do know about artificial intelligence (machine learning) is that it is very good (and very fast) at identifying patterns and matching them to other patterns.

As a mathematician friend once explained it to me:

“AI is just another tool in the statistician’s toolbox.”

The research team certainly are not claiming to have decoded every item of cave art from this period; or that every piece of art fits with their hypothesis.

However, it’s interesting to speculate about the scope for applying AI’s pattern-matching prowess to an even wider set of images than feature in this recent study. How widespread was it? What came before it, and how did it evolve?

And finally…

Of course, the fundamental achievement of Bacon & co is that they make the case for intellectual capacities developing at a much earlier stage in human evolution than was previously believed; but for me, it's also interesting to link this back to the works on show at the ODI, and wonder: is this art as data, or data as art?

Member discussion